Nothing to see here...

Earlier this year I ran a photography workshop at a location in the South Downs National Park. We were lucky to get lots of sunshine on this spring afternoon. At the beginning of the session, one of the guests said to me “I don’t really see anything interesting here, can you tell me what I should be focusing my attention on?” Then he mentioned his frequent photographic trips to Norway and how inspired he felt by its scenery. How he’d never needed to think hard about what to photograph there, but was at a loss on the South Downs.

Hazy afternoon in late May.

Now, comparing the tame agricultural scenery of Sussex to the wild, pristine beauty of Norwegian fjords is a bit unfair. Still, at that particular moment I couldn’t disagree with him. I’ve taken numerous successful photos at that exact spot over the span of more than 15 years. But right then I could see nothing that would compel me to get the camera out of the bag (if I’d had it on me). Things slowly started to shift, however, as the afternoon progressed. In the end everyone came away with some decent images from the session…

Imagination, anticipation, planning

Technical ability, eye for composition, skilful use of light are all fundamental elements of a landscape photographer’s craft, obviously. A much less obvious part of the skill set is imagination.

Great landscape images are hardly ever given to us on a silver platter. Extraordinary moments are rare and fleeting. Even dramatic scenery when captured in random conditions usually translates to unimpressive pictures. (And the bar for excellence is higher when dealing with more understated and subtle landscapes, like the South Downs.)

Being able to anticipate changes in the atmospheric conditions, to envisage the scenery in different lighting, at a different time of day or year, and to plan accordingly can go a long way towards ensuring that we get good photos more consistently. It can help us avoid wasting time and effort on while goose chases, and instead focus on locations or viewpoints likely to produce results in a given situation.

Mid afternoon in late March, taken during a workshop. After a brief hail storm at the beginning, which got us soaked, passing clouds created some good opportunities for maybe 20 minutes. Afterwards, the closer it got to sunset, the blander and more nondescript everything became…

Tactics and strategy

In the immediate context of a single outing, this kind of anticipation can lead to a “tactical plan” to get the most out of the limited time we have on location. On a grander scale, imagination (aided by a few tools) can provide the basis for a long-term strategy, when making plans for local excursions as well as trips to far-flung destinations throughout the year.

And thankfully, photographic imagination and anticipation are not an innate talent available to a select few. Like the technical side of photography, it’s a skill that can be learned and honed through observation, analysis, and practice. I’ll try to illustrate these ideas using the very location mentioned in the opening anecdote as an example.

Useful tools

There is a handful of tools I use regularly when planning local outings or preparing for longer trips.

- Ordnance Survey (OS) maps. If you photograph outside the UK, any topographic hiking maps will serve the same purpose.

- The Photographer’s Ephemeris (TPE) – to track the sun’s (and the moon’s) position in the sky. Free to use as a web-based application.

- Satellite and aerial imagery

- Google street view

- Travel guides (printed and online)

- Image research – particularly when preparing for a trip to a new place, I like to see pictures taken by other competent photographers to get a sense of what’s available.

First impressions

This specific area near Lewes was recommended to me some time in 2009 by a man born and bred in Sussex. Although not a photographer himself, he evidently had deep appreciation for the countryside, and suggested to me a range of places to explore across East and West Sussex. Most of his recommendations, various remote villages, were practically inaccessible to me, as I didn’t have a car at my disposal back then. Luckily, this one spot was only a 20-minute bus ride away, and then a short walk from the bus stop.

I’d never seen any photos taken in that area. Yet, from my initial research (looking at maps, terrain relief, satellite images) I suspected the spot should offer good opportunities to practise “long lens” landscape. By late 2009 I had already developed my telephoto approach to photographing the South Downs (read more about it). I knew what kind of lie of the land, vantage points, and lighting were likely to produce the effects I was after.

The snaps from my very first visit to the location haven’t survived. This is the closest “stand-in” I was able to find in my archives, taken 2-3 months afterwards. The originals looked worse: no tractor and not a hint of any directional lighting.

In my eagerness I to check it out, I didn’t wait for a day of “good” weather. Instead, I went there at the earliest opportunity – a dreary November afternoon. The scenery looked a lot worse on that day than it did at any time during the recent workshop. Overcast skies, slight drizzle, featureless taupe fields, hills blending into each other. Nonetheless, it got me quite excited straight away. The “cogs” in my brain started churning, visualising scenarios which would allow me to do this scenery justice in my photos.

Unsurprisingly, that virgin trip didn’t yield any significant photographic outcomes. I remember having taken a handful of snaps as a memento for future outings. Those photos are nowhere to be found in my archives now, I must have since deleted them since they were rather worthless. But they served their purpose at the time, as a reminder of what I could potentially achieve at that locale.

Only a couple of weeks after I took the previous picture, I was able to get this (in late February 2010). The weather was finally on my side, and the result was very close to what I’d seen “in my mind’s eye” when I first set foot at this location a few months before.

Coming up with a plan of attack

Armed now with some first-hand experience, I began to plan my next steps. The lie of the land and natural obstacles narrowed any good views to the south-west directions. When I checked them against the position of the sun at different seasons (using TPE), it became clear that this was primarily an afternoon location.

For most of the year, during early morning hours the sun would be somewhere behind the camera, making for flat lighting, which wouldn’t lend any depth to the landscape. Besides, much of the scenery would likely be plunged in the shadows until the sun was much higher in the sky and any magic long gone. The only exception seemed to be deep winter, when the rising sun would illuminate the land from the side, and that could indeed create good opportunities.

A few months later: May 2010.

Otherwise, from my studies of the terrain relief and the sun’s position in the sky, and from observations made in the field, I’d concluded this area would be worth visiting and revisiting at any time of year in the latter part of the day. Around summer solstice, the sun rays would be hitting the landscape from the side in the evening. During the shortest days, I might have the sun directly in front of me before sunset, depending on where exactly I pointed the camera. Between those two extremes, the sunlight would be coming from somewhere in front of the camera. So, exactly the kind of lighting I favour.

All I needed now was for some decent weather to coincide with my availability…

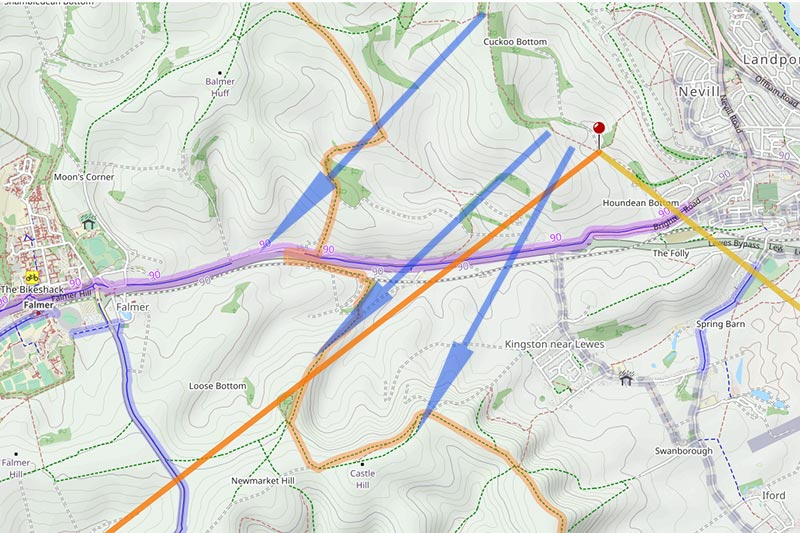

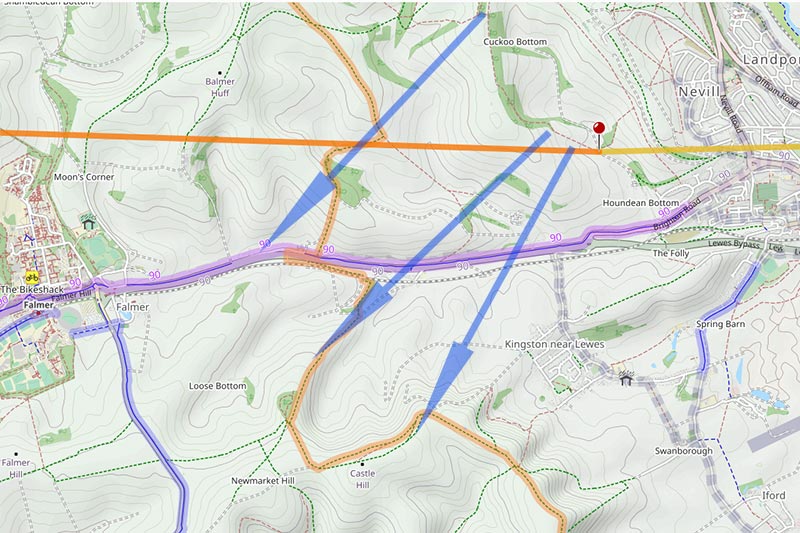

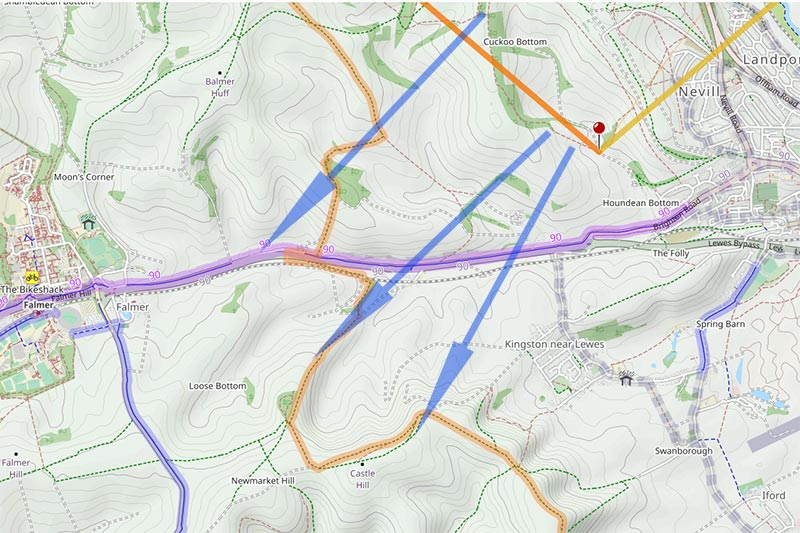

The Photographer’s Ephemeris is one of the few tools I use regularly when planning outings and trips. In the screenshots below the yellow and orange lines represent the sun’s position at sunrise and sunset. The blue arrows (added by me) indicate the available views. As you can see, between spring and autumn, the sun rises behind the camera when looking south west; in the summer even directly behind it. Therefore, in my view this is primarily an afternoon location, given my preferred kind of lighting; it can possibly offer opportunities in the morning only during the shortest days. (Read more about my approach to lighting in landscape photography)

Winter solstice

Equinox

Summer solstice

Keeping at it - across the seasons

I have since visited this little spot countless times in different seasons, and taken hundreds upon hundreds of photos. Of course, I didn’t always get what I wanted – the weather so often plays tricks on photographers – despite my vivid imagination and best planning efforts. Still, I’ve had a fair share of good moments here since 2009, and managed to capture a variety of moods and flavours. Below are a few more examples showing how much this one location has to offer.

A dusting of snow in January. Late afternoon.

Early morning in January. A short “window of opportunity” during the year when the location works after sunrise.

Same location in April, taken during another workshop. The sun was still high in the sky at this stage, and the lighting it produced quite harsh and not very nuanced. I was observing the movement of clouds across the sky and waiting for moments when they would cast shadows in “strategic” places, adding more depth and interest to the scene.

While the spot lends itself best to telephoto treatment, on this occasion in early June I got captivated by the colour harmony at sunset and had to use a wide angle to try to capture it.

Late afternoon in July. Taken during a 1-1 workshop.

Shortly before sunset in mid September.

Closing thoughts

This little offering is a case study of only one particular location and one approach to landscape photography. Different kinds of scenery and photographic styles may entail other considerations, not just the position of the sun in the sky or obstructions blocking the light.

For instance, for seascapes you’ll need to be aware of tide phases, possibly the direction and strength of wind; when preparing for a blue hour session, you’ll need to know exactly when the sun sets (or rises) to time it well – since the window of opportunity is so short – and consider the light sources in your potential scenes, so as to pick the best perspectives and angles for a perfect blend of light.

Also, it’s much easier to envisage your scene in different conditions if you already have first-hand experience of it (or while you’re on location), as compared to imagining what you could achieve based solely on satellite imagery, street view or other people’s photos. Still, it’s all part of the same broader skill: being able to create mental images, make predictions, and then decisions informed by them – to get the most out of the time you have.

So, if up until this point you’ve only relied on pot luck in your landscape adventures, I hope I’ve convinced you that spending just a little bit of time in preparation and “visualisation” can make a difference in the quality of your landscape photography in the long run. And although it may seem like a difficult skill to master, I promise, with time and practice, it will become a second nature. Good luck!

Thank you for reading. Check out other similar articles in my Landscape Photography is Simple “blog”. Or click on a random post below.

Case study: a seascape from idea to postproduction Everyone has